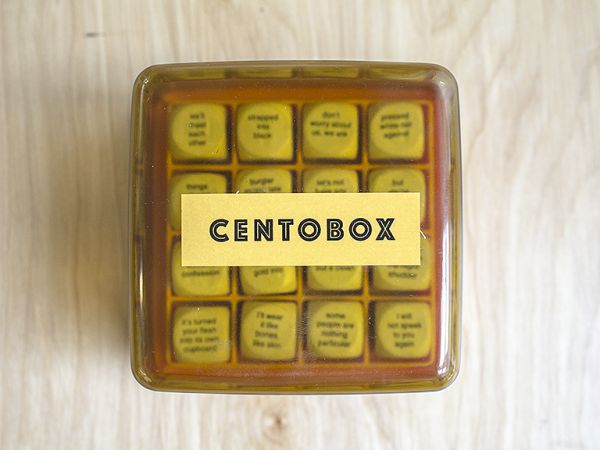

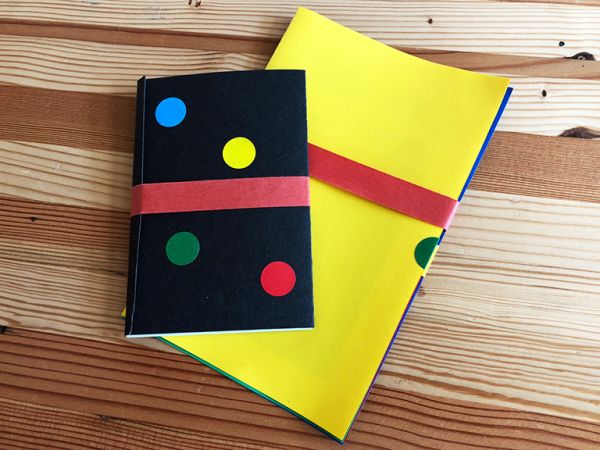

CENTO BOX

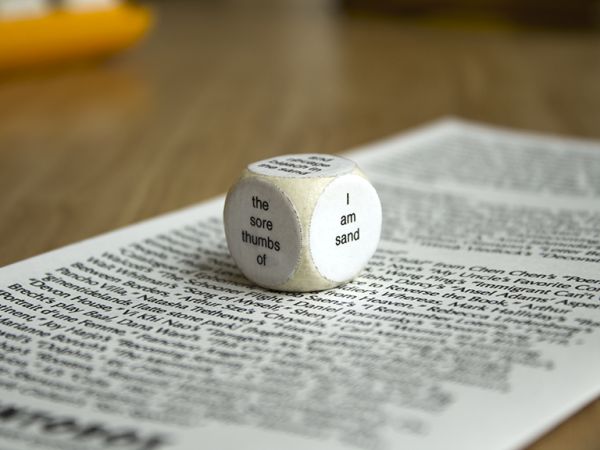

From the Latin word for "patchwork," the cento is a poetic form made up of lines from poems by other poets. The word cento is also Italian for one hundred—some centos are exactly 100 lines long.

In CENTO BOX, 16 dice showcase lines from 16 different contemporary centos (see the full list of sources here). Shaking the box allows the player to explore 2,821,109,907,456 different poem combinations sourced from texts written by more than 250 individuals. A three-minute sand timer is included if the player wishes to operate under further constraint. Also included is a detailed instructional booklet outlining the rules of play and source citations for each of the 16 dice.

CENTO BOX is a exploration of found poetry, appropriation, and remixing—themes that carry throughout my work as a writer and artist. When writing a poem using CENTO BOX, the player is borrowing from not only the centos, but also the poems from which the centos were made. The questions only multiply from there—what is an original thought versus a borrowed phrase? Where is the boundary that separates whose words are whose, and who decides? Should there be a boundary? Where is the line between exploitation and the ethical use of language? These ruminations lead to a more universal question that many writers grapple with: what can be said that hasn’t already been said before?

We all create under some kind of constraint. Found poetry works for me because there is a ruleset, a limited playing field. It’s a language game that requires play, decision making, creativity, action.

CENTO BOX is stacked on a dusty game shelf, camouflaged in its unassuming package. Let your guests pull it out and shake the dice—what poems do they find? Place it on the corner of your desk, just beyond your laptop screen, inspiring you to let the words fall perfectly into place. Pulled from an archive a century from now, CENTO BOX will defy categorization, churning out poem after poem after poem.

About the artist

Erin Dorney

Erin Dorney is the author of I Am Not Famous Anymore: Poems after Shia LaBeouf (Mason Jar Press, June 2018). She is the recipient of a 2017 Artist Career Development Grant from the Prairie Lakes Regional Arts Council/McKnight Foundation; a 2017 Emerging Artist Residency at Tofte Lake Center; a 2016 Spruceton Inn Artist Residency; and was the first Modern Worker: Writer in Residence at Modern Art in Lancaster, PA. Her literary erasure art "Dystopia Erased" was featured as part of Made Here: Future, an urban walking gallery in the West Downtown Minneapolis Cultural District and her collaborative conceptual art installation "The Hidden Museum, 2018" is currently on display at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Erin is cofounder of FEAR NO LIT and volunteers with VIDA: Women in Literary Arts. You can find more of her writing plus projects and updates at erindorney.com.

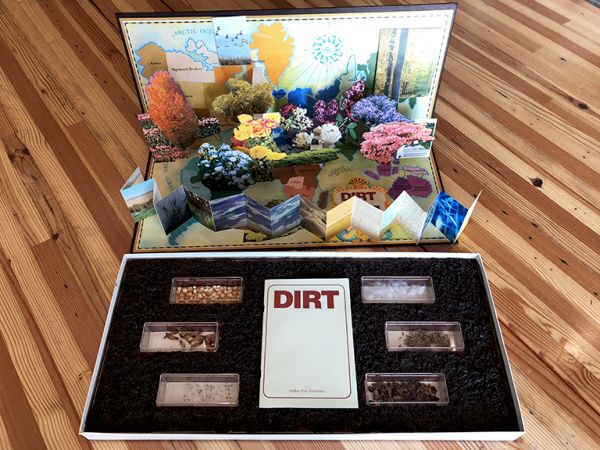

DIRT

My work as an artist is rooted in ideas of home and how I orient myself in terms of all the places I've lived. With RISK, I was thinking about the rules of the game and the ways that land is defined and occupied. I knew almost immediately that I wanted to replace the army pieces with seeds that conjured up a sense of my childhood in Nebraska.

With that in mind, I started gathering imagery for an accordion book that would replace the deck of cards and would incorporate elements of both the natural world and the nostalgia of childhood. I felt intimidated by the board itself until I started thinking about pop-up books and knew I wanted to turn the board into a three-dimensional garden. Using images cut from used gardening books, I pieced together flowers, bushes, and trees in shapes and colors that mimic the countries outlined on the board.

In naming the book, I wanted a word that I could use to visually replicate "RISK." Using two of the same letters, DIRT did the trick, plus it helps to keep the piece as a whole firmly planted in the earth.

About the artist

Amber Eve Anderson

Amber Eve Anderson is a multidisciplinary artist whose work uses images, objects, and language to explore themes of home and displacement, often combining aspects of the digital and the real. In 2016 she was a Baker Artist Award finalist—Baltimore-area awards totaling $85,000—and was awarded residencies at Wagon Station Encampment with Andrea Zittel in Joshua Tree, CA and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts in Nebraska City. Her work has been exhibited in group shows throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, Finland, Morocco, and Peru. Her first self-published book, Free to a Good Home, was purchased by the New York Public Library and is sold at Printed Matter, the world’s leading non-profit for artist books. She received her MFA in 2016 from the Mount Royal School of Art multidisciplinary MFA program at MICA in Baltimore, MD. She is currently a resident artist at School 33 and a regularly contributing writer to BmoreArt.

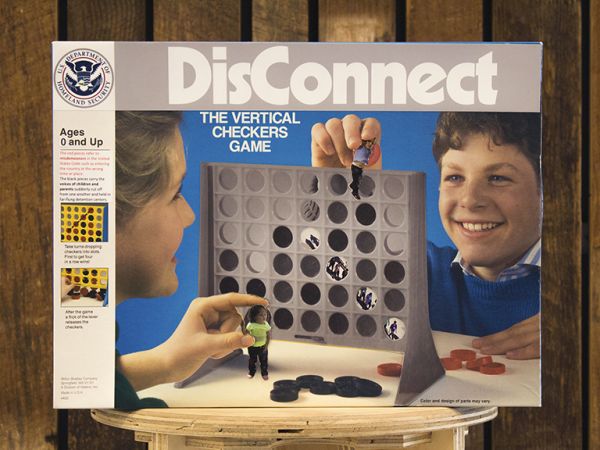

Disconnect

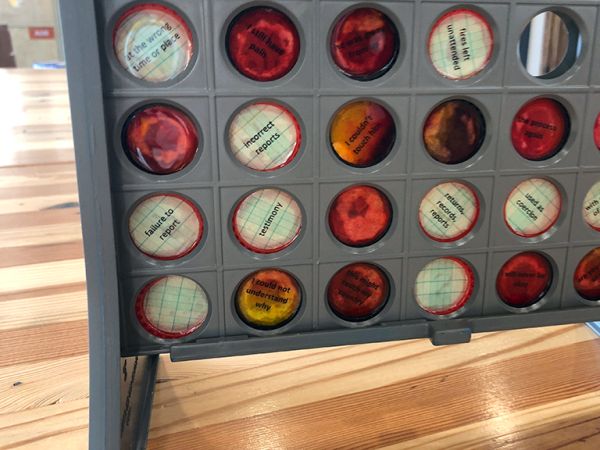

In Connect Four I love the way the pieces fall into place, the way everything is right in front of you but you still have to pay attention to all the possibilities. Since I'm always coming up with poetry games, I immediately thought it would be fun to add text to the individual pieces so that each game would produce new juxtapositions. A bit like Magnetic Poetry, but with the text also working vertically and diagonally. And a bit like Battleship in that the players look at different sides of the board; each has a different part of the story and reads the possibilities differently.

The challenge was to find or create a text that would respond well to this kind of play. I had a few ideas, but when I was still toying with them I read that the Trump administration was prosecuting and detaining everyone who crossed the border without prior permission and had begun separating children from their parents in the process. I noticed that crossing the border at the wrong time or place is a misdemeanor, and I wondered what a misdemeanor is. A wrong appearance, a lesser transgression, yes, but I couldn’t put my finger on what was wrong or lesser without knowing what else is a misdemeanor. So I dug up a table that listed all the federal laws containing misdemeanor penalties, and right away I saw “transporting water hyacinth.” And there were sponges and burros and telegraph cables, and the whole list seemed eerily reasonable, a window into a world of creatures and transactions and responsibilities and mistakes that could have but hadn’t necessarily harmed anyone.

So I knew I had to work with this list of misdemeanors somehow, this list of things that are, ordinarily, sort of reasonably penalized—impermissible behaviors peripheral to our system of mass incarceration. But I needed language from the families caught up in this travesty as well, the ones whose supposed misdemeanors were being used as an excuse for depriving them of their only stability: one another. Then the audio recording from one of the detention centers came out. As I worked, a few additional accounts were published, and I used some quotations from parents and children in these as well.

Now I had two sets of language and could begin seeing how they worked in relation to one another. The children and parents relate more basic and practical information; what the children need is simple and of profound importance. The misdemeanor texts, which I’d initially found whimsical, began to change in response to both the importance of the subject and the seriousness of the allegations that were coming out. They began to accuse: poor record-keeping, failure to report child abuse, using available relief as a means of coercion...weren't these the very things that were occurring? And they began to invite: interfering with an order of the court, letting a prisoner escape. Did they describe what we must not do, or what we must?

From the first mockup, the differences from other poetry games I'd tried were clear. The array was too complex, and the sanctity of the individual voices too important, to rely on game play to create sentences. I shifted more weight to the game pieces themselves: to the relationship between what was said on each side of the coin, the role of silence, and the ways that game pieces can be both plastic and precious. I decided to print the quotations from parents and children directly on paper my children had dyed for butterfly wings years ago. It felt right to use something worked by children, something transient and precious, that could have been discarded but wasn’t. For the misdemeanors, I used ledger paper my children had scored in one of their many raids of their grandfather’s office supplies. He’s a meticulous record-keeper who came to this country with his parents as a young child from a displaced persons camp.

There are a few problems I didn’t manage to solve in making this piece. One is the dislocation of using English and not identifying the national and indigenous groups involved (not all of which are known). Another is the emphasis on families, as if individuals without family, or those separated from family in other ways, are less important. Also mostly beyond the scope of this project, which focuses on the trauma of separation, is the treatment of the children and adults, including abuses that are still coming to light.

I hope that this game allows players to feel a disconnect between the desire to win and the need to listen to those for whom this is no game, and to reflect on possible connections between the language of law and the language of compassion.

About the artist

Amy Eisner

Amy Eisner teaches creative writing at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA).

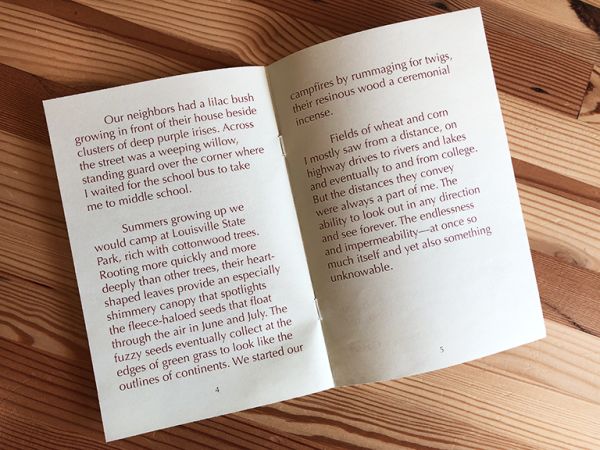

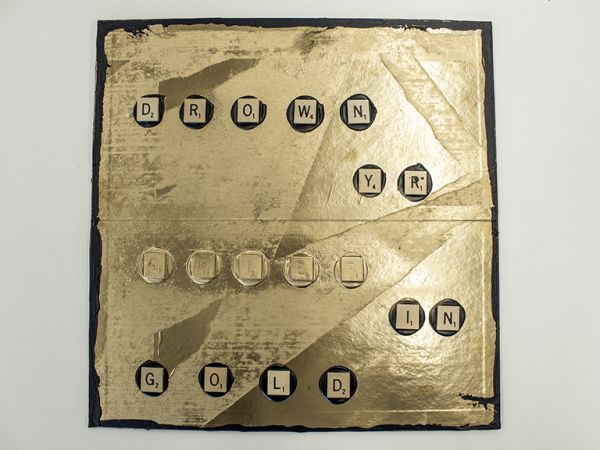

drown yr grief in gold

i spent a spell rearranging letters until settling on the language i wanted to highlight and spent the next spell playing with the board/box

About the artist

Sam Sax

sam sax is the author of Madness (Penguin, 2017) winner of The National Poetry Series and Bury It (Wesleyan University Press, 2018), winner of the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. He’s received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Lambda Literary, & the MacDowell Colony. He’s the two-time Bay Area Grand Slam Champion, author of four chapbooks & winner of the Gulf Coast Prize, The Iowa Review Award, & American Literary Award. His poems have appeared in BuzzFeed, The Nation, The New York Times, Poetry Magazine, Tin House + other journals.

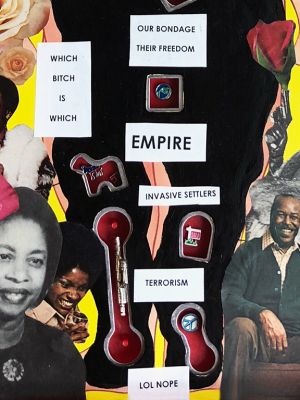

Operation USA

“The Game—Done!”

In Western history the racist fetishizing, caricature, and stereotypes of Black people is a legacy of white supremacist domination- a tradition continuing to this day based on fear, envy guilt. We have suffered from their delusions- that to be Black is something to be feared, dehumanized, and eradicated, as if we are a “pest” that can be controlled and scourged from the planet. We’re still here. Despite their beloved enterprise reigning terror on our lives. But what can we do to try to undo/reverse/block the psychic and psychological mess their pathetic magic brings in the pursuit of ultimate power?

“Cavity Sam” is the name of the patient, according to the original directions to the game “Operation.” Uncle Sam is on the operating table rotting from the inside out from his lies, delusions, and deceits, is the keeper of a terminal illness called manifest destiny, called colonialism, called capitalism. Through generations of persecution in this global circle jerk career of hate Uncle Sam projects his own dehumanization onto his victims, and in the end who here is the real caricature, stereotype, and fetish object?

Players, get ready. Live your lives: dancing, dreaming, loving. Fighting, writing, studying. We’ve struggled so much and frankly, it’s not on us to undo the bad juju tied like a noose around Mother Earth. But we’re intimate with these bonds of hate. So if you’re feeling good enough to try, feeling invincible after a memorable night, pick up a scalpel. Dominate these forces, examine them, throw them in the biohazard trash bin. Laugh at how ridiculous their efforts, how monstrous, how desperate they are to live in their nostalgic paradise of death and laugh a terrible laugh—that high/low tome of joy sounding out the blues and torrential sunshine of our fine-tuned souls. We’ve known your secrets all this time, Uncle Sam. Prepare yourself for the continuation of our reckonings.

About the artist

Nikki Wallschlaeger

Nikki Wallschlaeger’s work has been featured or is forthcoming in The Nation, Georgia Review, Brick, Witness, and POETRY. She is the author of the full-length collections Houses (Horseless Press 2015) and Crawlspace (Bloof 2017) as well as the graphic chapbook I Hate Telling You How I Really Feel from Bloof Books (2016). She lives in Wisconsin.

Tw*ster

I have always found Twister's highly physical game play incredibly inspiring. For this project, I was interested in exploring this embodied nature and using it to think about ways in which games create complex, playful spaces for intimacy, permission, and control.

About the artist

Sam Sheffield

Sam Sheffield is an artist and game designer interested in exploring control, embodiment, and intimacy through play.