The Action of Light

When I first unpacked my lunch box, I felt very unsure about what my next step might be. I tried looking at the box from different angles. As soon as I set it on one of its short sides, I saw a box camera. After that, the ideas came rushing in.

I've been thinking a lot lately about the sometimes tenuous relationship between images and texts, including the captions we choose to put on photographs (some purely descriptive, some more evocative or seemingly unrelated), and have been interested in writing a collection that incorporates photos accompanied by text about what is unseen in the photos.

Inspired by Anne Carson's book Float (where each poem or set of poems is bound separately so that you can deal them out and encounter them in any order you like), I decided to create a set of image and poem "photographs" contained in the camera. It was important to me to introduce as much randomness into the project as possible, to see where connections and themes might be revealed, depending on the reader or viewer's gaze.

For the images, I randomly selected 20 of my own photographs taken in 2016. For the poems, I began with a freely available online source text and used die rolls to choose chapters and then pages within chapters from which to draw words. The source text is The History and Practice of the Art of Photography, by Henry Hunt Snelling (published by G. P. Putnam, 155 Broadway, 1849).

To write each poem, I chose specific words or phrases from the selected pages. I never altered the order of the words as they appeared in the source text, and I never added words not included in the source text, though I often changed punctuation and sometimes used only parts of words. I then paired photos with poems, again randomly. Since the source text describes early methods of photography, I found that many themes (light, shadow, equipment, chemicals, and time) easily emerged, but in some unexpected ways.

For the box itself, I decided to create the suggestion of a camera, functioning as a container into which the photo poems were "loaded" and then later extracted for viewing. (I'd also thought to use the thermos as a lens of some sort, but my experiments with that were unsatisfactory.) My hope is that the reader will remove the cards and reorder them—some image-side up, some word-side up—to make their own collections of poems and photographs. To encourage random selection, I included a 20-sided die as the "viewfinder" at the top of the camera, which can be rolled by turning the box and then used to select a card from the stack.

I wrote many of these poems on the days just before and after the August 2017 solar eclipse, when the action of light was very much on my mind.

About the artist

Rebecca Siegel

Rebecca Siegel is a writer and photographer. Her poetry and essays have appeared online and in several journals, including Straightforward Poetry and Remedy Magazine. Her participation in the Found Poetry Review's 2015 PoMoSco project sparked her interest in found poetry. Since then she has completed several other found poetry projects, including "Shackleton Found" and "The Found Now." She lives in Vermont with her husband and daughter.

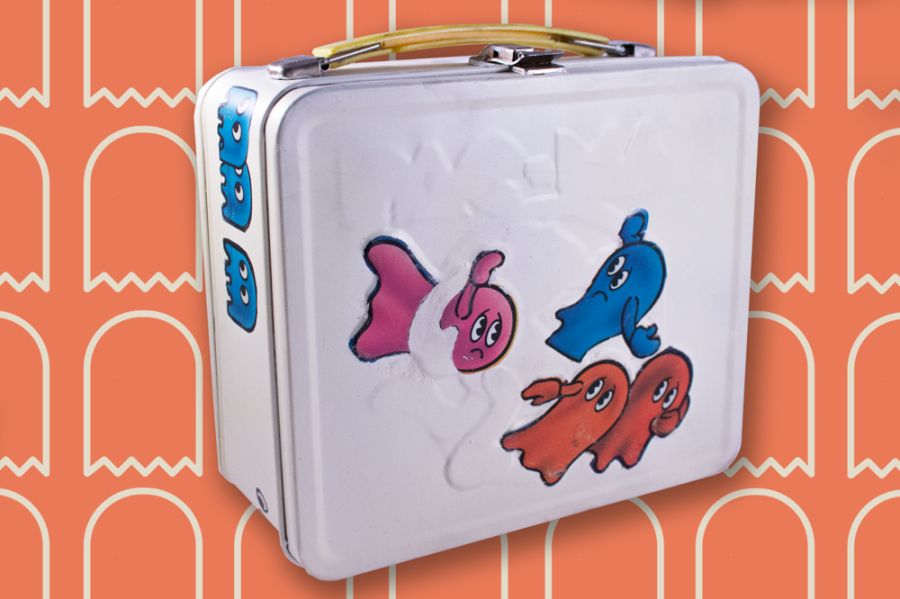

What The Ghost Of A Ghost Is

My work generally concerns memory and media, and I was very excited to receive a lunchbox rich in connections to both for this project. When I opened the package containing it, I thought of my 80s childhood spent obsessing over early video games and the new worlds they represented to me. With Pac-Man in particular, I was always confused by the variations among the characters in the game, on the sides of the machine, and in the total saturation of marketing imagery reflected in toys, cartoons, songs, and even a pair of pajamas I received for Christmas, 1980 (which I slept in before I even knew what Pac Man was). Opening the package in 2017, though, I was immediately struck by the sadness of the ghosts represented on the lunch box—they are either being pursued or ingested by Pac Man—and that got me considering their story more deeply than I had before.

I decided to use this piece to foreground the experience of those ghosts as a way of exploring how a game like Pac-Man exists in media and in memory, and where, perhaps, our own ghosts and emotions encode themselves along the way. The idea that these characters, who begin as ghosts, exist in a cycle of being destroyed and reborn was particularly interesting to me—the way this narrative applied to a particular instance of play-in-need-of-a-story raises questions about representation, permanence, and regeneration.

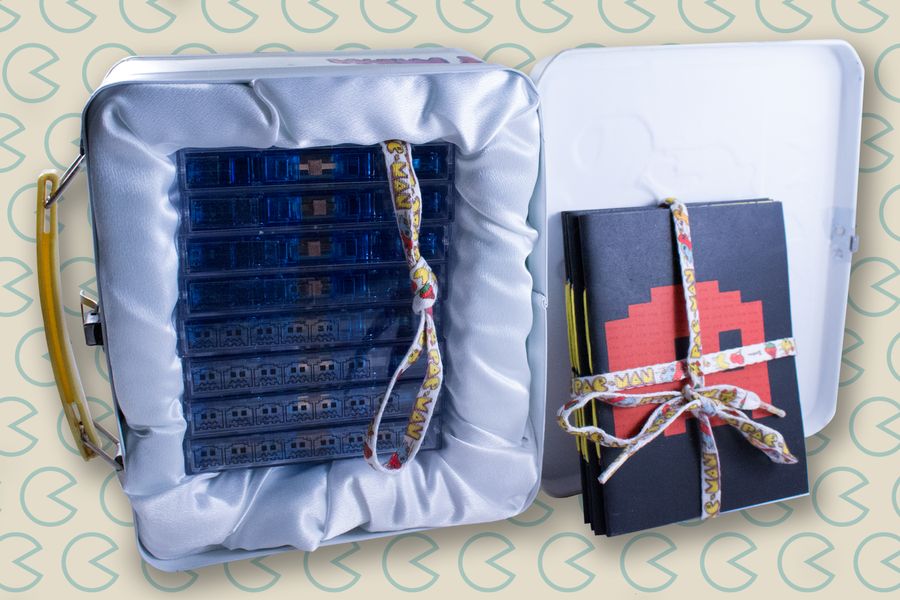

Considering the capaciousness of the lunchbox, I decided to preserve its ability to contain, and eventually grew to see it as a coffin-like reliquary in which to house artifacts and evidence from this story. I'm interested in the effects software, hardware, and human experience have on each other, the way their associated constraints collide and occlude and conspire. I decided to produce items for the reliquary which draw attention to how the game exists within and beyond these realms. I located the original source code of the game (which I lightly compressed and encrypted by removing 13,000 spaces) and created a series of four booklets across which to distribute it, each dedicated to one of the ghost characters. While rendered mostly useless as computer code, the material text in the booklets presents readers with the rhythmic possibilities of that text and a tangible, static access to how the game exists in computer memory.

Also contained in the box is an octet of cassette tapes: second, fourth, sixth, eighth, tenth, twelfth, fourteenth, and sixteenth generation duplicates of two recordings derived from the game. Side A on each cassette contains fifteen minutes of gameplay audio (most notably the near constant trill of the ghosts) looped and filtered through analogue synthesizers and subjected to other effects. Side B of each cassette contains a computer vocalization of the source code (compressed down to around 15 minutes from an original 9+ hour recording). Through the various generations of recording, the original audio recedes more and more into the cacophony produced by the dynamics of the audio signal encountering the limits of analog recording technology. As with the source code itself, the recordings require hardware that is both obsolete and subject to much contemporary nostalgia for playback.

On the outside of the lunchbox, I did my best to excise everything that wasn't the ghosts, to tune viewers into the peril in their movement and the terror in their eyes. My hope is that this adds a measure of emotional gravity to reflection on the artifacts stored inside.

About the artist

Patrick Williams

Patrick Williams is a poet, artist, and academic librarian living in Central New York. He is the hands behind typewriter.city, a micropress launched in 2016 to release small-run, handmade books of tiny projects that reward close attention in stolen moments. His chapbook Hygiene in Reading was awarded the 2015 Chris Toll Memorial Prize and was released by Publishing Genius in 2016. He edits Really System, the journal of poetry and extensible poetics. He received an MS & PhD in Information Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. Find him at patrickwilliamsintext.com.

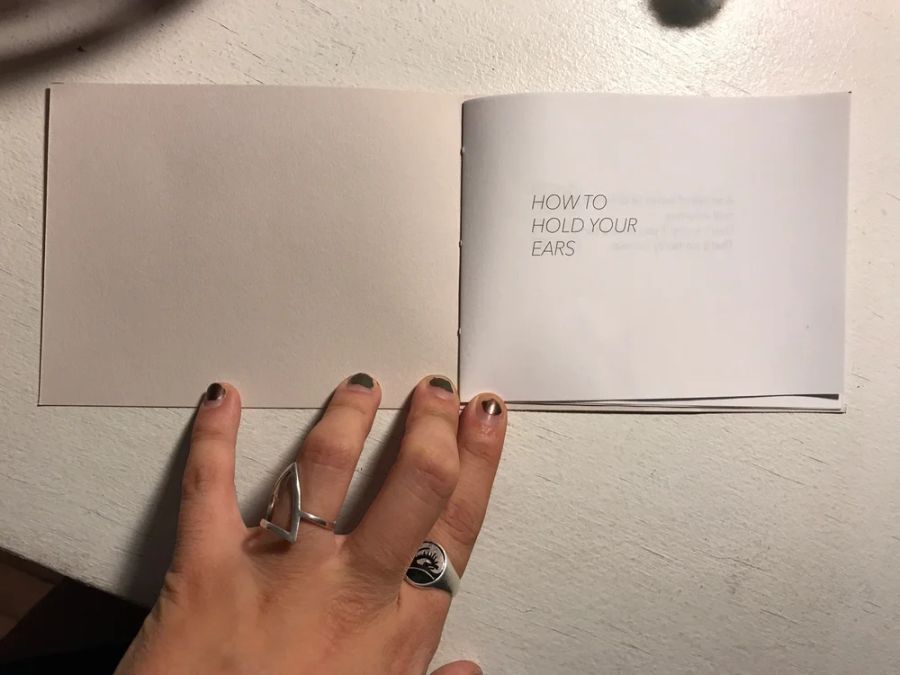

How to Hold Your Ears

The project was a great excuse to watch tv and call it "work." I watched various episodes of the original Mickey Mouse Club, The New Mickey Mouse Club, which is the one that this lunchbox stems from, MMC (the nineties iteration), and several documentaries about the show itself. Through the process of watching, I became interested in the community aspect of the show and it turned my attention to one of the most important aspects of community: listening.

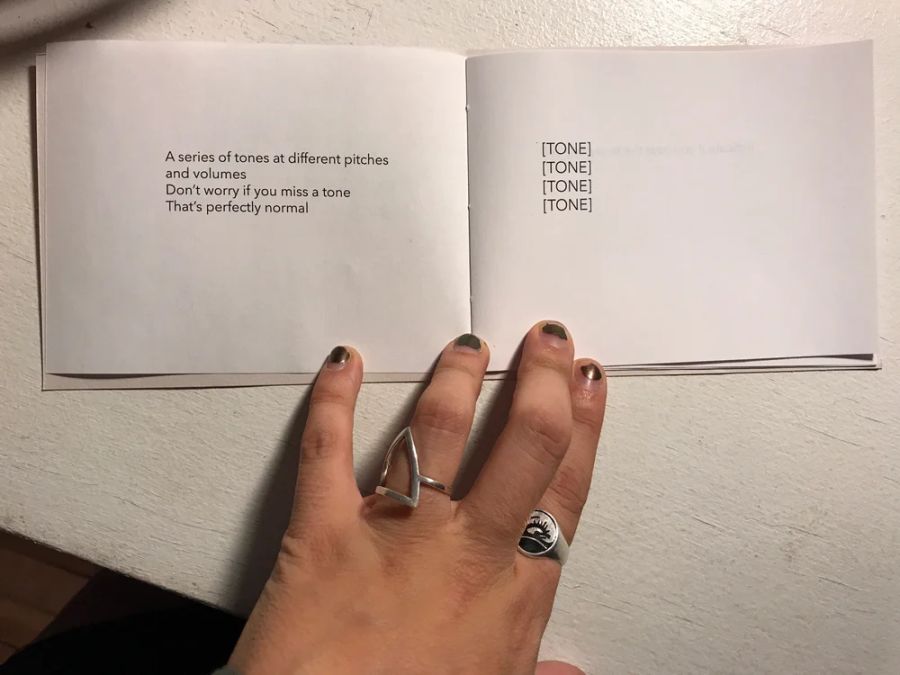

Since ears are such an iconic symbol of the Mickey Mouse franchise, I rolled with that mode to explore the lines as sound speech. From there, I studied hearing tests, which use audiograms to record the patient's data. I then arranged the lines I collected from viewing the material to follow an audiogrammatic structure. As you read the text, the lines themselves start becoming the tones used to supply data to the audiogram, so the system fails itself.

Since the show is so tied to performance, I found it important to make these materials performative themselves. I needle-felted white and blue wool together to create balls that performers can stuff their ears with along with instructions on how to perform the piece. In essence, the lunchbox and thermos become a toolkit to form your own Mickey Mouse Club or strange hearing test, which to me, became the same thing. The tradition of commodifying our bodies for entertainment is a long one and this piece serves to show the mere absurdity of that.

About the artist

Natasha Mijares

Natasha Mijares is an artist, writer, curator, and educator. She received her MFA in Writing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has exhibited at MECA International Art Fair in Puerto Rico, Sullivan Galleries, TCC Chicago, and Locust Projects. She has been published in Calamity, Vinyl Poetry, Bear Review, and has work forthcoming from Hypertext Magazine.

Joke Explosion

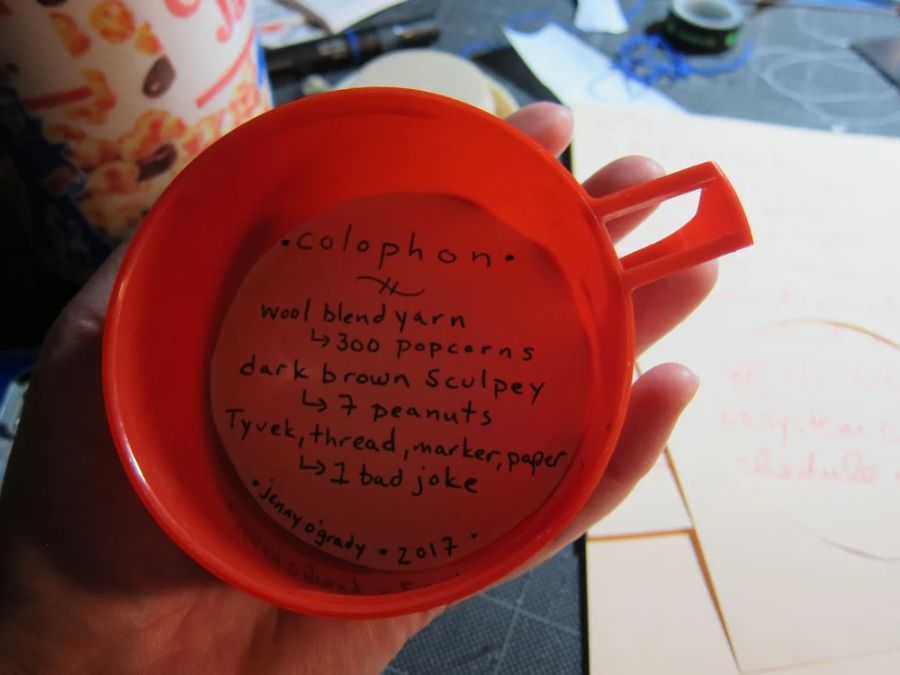

When I saw my lunchbox for the first time, I was SO excited. I have always loved the packaging for Cracker Jacks -- especially the tiny folded joke prize booklets. I love the little structures, and I adore the fact that the jokes are always terrible. Thinking on this, I was reminded of the way, as kids in the cafeteria, we would try to make each other laugh so hard we'd spray our milk out of our mouths (or, worse, our noses). Thus, this project was born.

I use fabrics and Tyvek a lot in my work, so I decided it would be a fun challenge to make caramel corn out of yarn knots and Sculpey peanuts. If you dig into the pile of popcorn, you'll find the Cracker Jack prize -- an embroidered envelope inviting you to "Guess What's Inside?" Inside the envelope is a joke book containing my favorite bad joke in the world: What's brown and sticky? (Answer: A stick.)

Assuming you're "eating" the popcorn, you're also "drinking" the milk inside the Thermos. And since the joke is so ridiculously funny/bad, the poem inside the Thermos (written on a spiral of droplet-covered white Tyvek) is a haiku about losing said milk to the hilarity.

It's quite possible this is only funny to me...but that's where the box took me. And, I'm guessing I'm not the only one ever to shoot milk out of her nose. :)

About the artist

Jenny O'Grady

A native of Maryland's Eastern Shore, Jenny O'Grady writes and makes book sculptures in Baltimore. By day, she edits UMBC Magazine; by night, she runs The Light Ekphrastic, a quarterly ekphrastic journal that pairs writers and visual artists from all over the world to create new works online. The Baker Artist Awards named Jenny a 2013 winner for her book arts, and she was the 2013-14 writer-in-residence for the Howard County Poetry & Literature Society, based in Columbia, Maryland.

Portable Crystal Grid

As soon as the lunchbox arrived I understood it was to be a portable crystal grid. I have a very large grid made of crystals collected as gifts, etc., from over thirty years and this grid has been a healing device for myself and friends. The lunchbox is the perfect size for a compact grid. The amethyst enhances your creative capacities. The rose quartz opens the heart chakra. The carnelian is an empowerment stone, motivating us to span the distance between where we are and what we want to achieve.

The base of the grid is planed oak that I coated in an ochre stain to give a solid, grounding place for the crystals, as well as to help contain their energies. The crystals were mounted with a clear industrial adhesive with the amethyst, rose quartz and carnelian on the east and west edges of the grid, and small clear quartz chards directing their frequencies to the center clear quartz stone. That center stone then holds the transmissions of the other crystals. There are also pieces of amethyst, rose quartz and carnelian inside the thermos to infuse drinking water to compound the grid experience with having an internal charge as well as the external from the grid itself. The copper bracelet is a conducting device which helps direct the grid's energy into your body. The bracelet is kept around a small pillow (sock with pillow stuffing) which has a rectangular chunk of selenite crystal inside it. Selenite's job is to constantly clean the grid, keeping the energy source of the crystals clear and viable for use

About the artist

CAConrad

CAConrad is the author of 9 books of poetry and essays and the latest is titled While Standing In Line For Death from Wave Books (2017). He is a Pew Fellow and has also received fellowships from Lannan Foundation, MacDowell Colony, Headlands Center for the Arts, Banff, RADAR, Flying Ojbect and Ucross. For his books, essays, and details on the documentary "The Book of Conrad" (from Delinquent Films 2016), please visit http://bit.ly/88CAConrad.

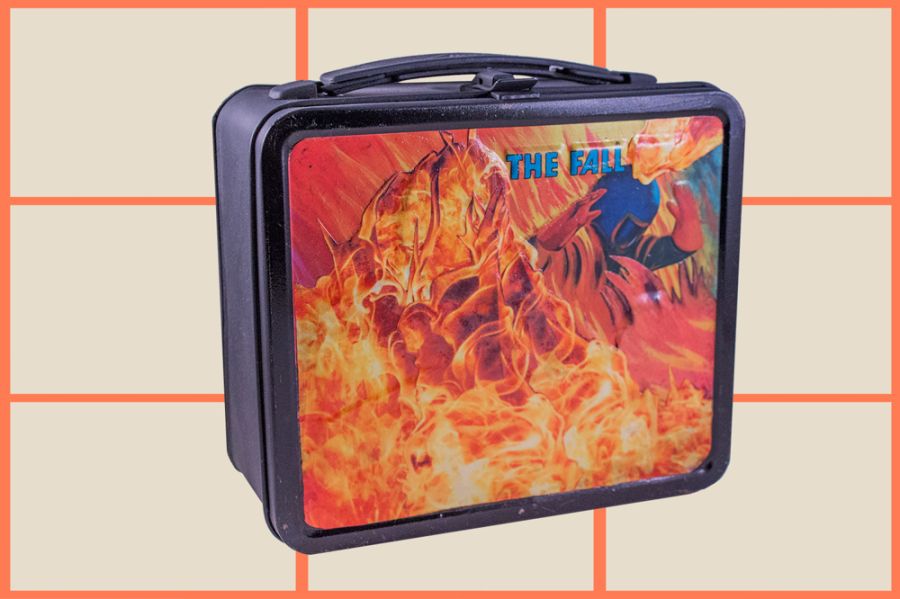

The Fall

There appears today a consensus that the USA has entered an era of apocalyptic decline, that “The Fall” is finally upon us.

I am suspicious of this thinking.

From the moment a European stepped onto this continent, from the moment one “American” enslaved another, we have remained falling. Rather than a new creation, our current president is a very old one. Rather than speak his name, I call our president “Manifest Destiny.” Our destiny is perpetual fall.

There is no single “Last Judgement.” There are no end days. There is only today. Today is everyday. So, today we get to work.

About the artist

Johnny Damm

Johnny Damm is the author of The Science of Things Familiar (The Operating System, 2017), a blend of essay/comics/poetics described by Publisher's Weekly as "sophisticated and delightfully bizarre" (starred review). His work has also appeared in three chapbooks, including Your Favorite Song (Battle Stories) (Essay Press 2016), and in journals including Poetry, DIAGRAM, The Rumpus, Drunken Boat, and elsewhere.

He teaches at San Jose State University and serves as editor-in-chief of A Bad Penny Review and Opo Books & Objects. See more of his work at johnnydamm.com.

Weather, Ritual, Black Stars

This project was a huge experiment for me. Though I love working with odd materials, reclaiming mundane, often discarded things, when I got the lunchbox I admit I was stumped. I'd never heard of the television show it celebrated, and the images didn't particularly speak to me (although the colors did).

So I sat with it, or, rather, it sat on a chair. I glued beautiful blue marbles into it, but then ripped them out. I felt stymied, strangely uninspired by the shape of the thing.

But what is a box? A container, yes, but also a secret. I remember my elementary school lunchboxes—not metal, but cloth, and easily made sticky by a spilled drink or squished apple. A box—a lunchbox—can hold this mess, but this mess also seeps out, smells, makes gluey the body.

What would happen if I opened it, deconstructed it? What would the story become then?

I went out looking for someone to cut my lunchbox. I went to the locksmith. A man came up to me and asked if I was looking for someone to play with my lunchbox. I said, No, I'm looking for someone to cut it. He said, This is what I do, and gave me his card.

I considered having the man cut the lunchbox, I did. But it didn't feel quite right. My sister the artist, visiting for several days, encouraged me to keep looking. A woman at the art store recommended a makerspace, a hacker's night, the tool library. She said, You can do this yourself.

I found the Station North Tool Library, asked if someone there could cut the box. They were adamant: I really could do it myself. They were encouraging, helpful, unjudgmental, patient with my questions. They lavished me with supplies. I left excited, empowered, and a new annual member.

And so the lunchbox opened up. I began outside one hot day, but my neighbor, seeing me, reminded me that I could use the basement workspace. Another space still opened. I sat there, sawing, worried about the noise I was making, worried about the sharp edges I was creating, until I stopped worrying and just did it. I cut myself, bled a little. Eventually, the saw gave way to the snips—faster, more precise, and satisfying. All these tools I hadn't used. Tools women often aren't taught to use.

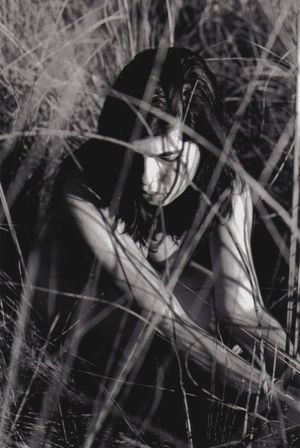

The thing took shape, developed new character. Stories became more evident to me. Suddenly, the images were rich, full of mystery. One night, I painted words on with chalk markers, let them sit and stew. I reclaimed other materials—nail polish, embroidery thread—thinking of teenage girlhood, but also because they're what I have around; I am generally inspired by what is just around.

The end—this folding and unfolding book—still feels new to me, slightly dangerous. But, as I started, an experiment. Which is all I ever hope for. The process is the thing, the box undone and remade.

About the artist

Anne Marie Rooney

Anne Marie Rooney is the author of Spitshine (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2012) and No Beautiful (Carnegie Mellon University Press, forthcoming 2018), as well as chapbooks from The Cupboard and Birds of Lace. Her poetry has been featured in the Best American Poetry and Best New Poets anthologies, and been the recipient of the Iowa Review Award, the Gulf Coast Poetry Prize, the Greg Grummer Poetry Award, the So to Speak Poetry Prize, a Barbara Deming Memorial Grant, and others.

She is a founding member of the poetry collective Line Assembly. Since 2011, she has been collaborating with her sister, the painter Julia Rooney, on a mail project that uses the USPS as a method of production, distribution, and exhibition. She has taught interdisciplinary, arts-integrated classes for kindergarteners through senior citizens, in venues ranging from museums to community centers to libraries to schools.

Born and raised in New York City, she currently lives in Baltimore, and is a student in Expressive Arts Therapy. Read more at stolenplums.com.