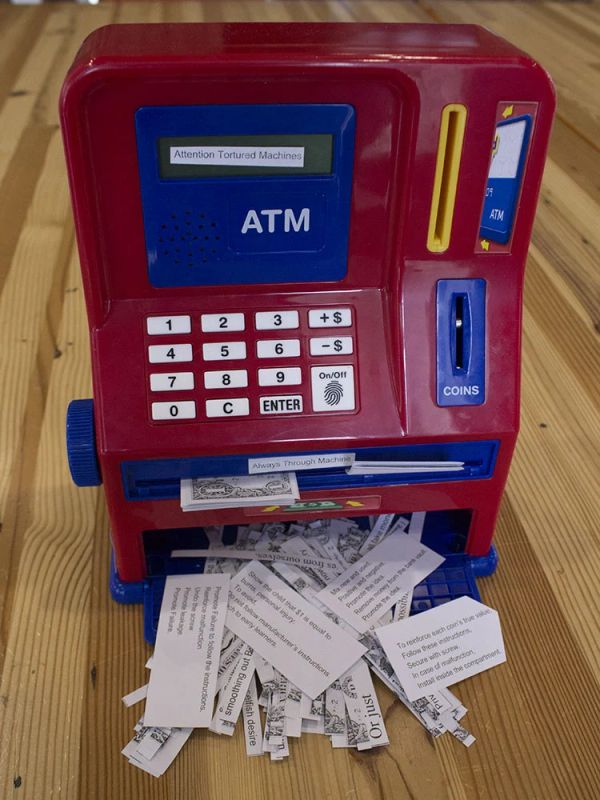

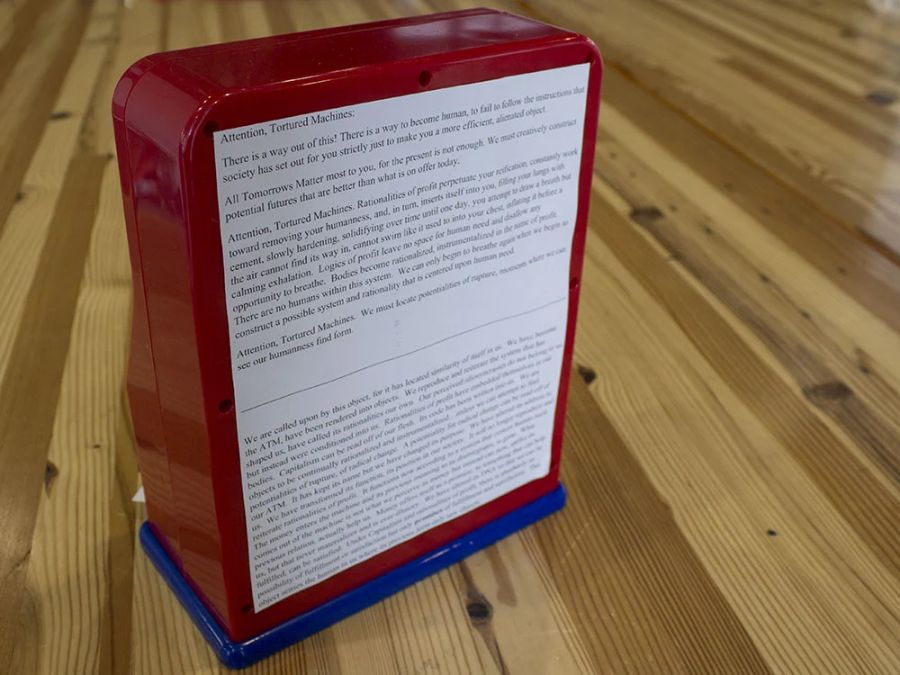

Attention, Tortured Machines

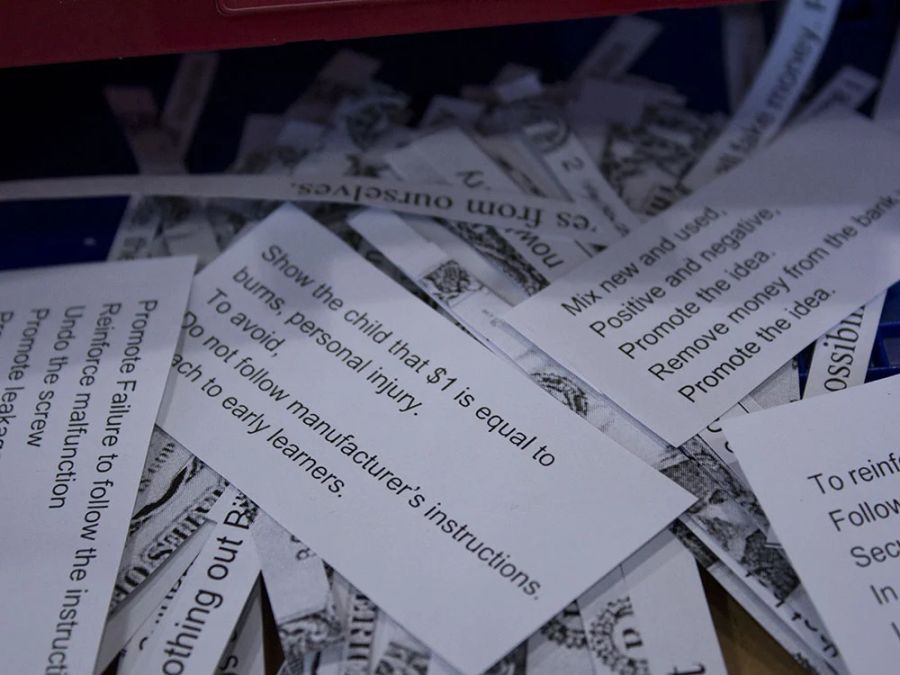

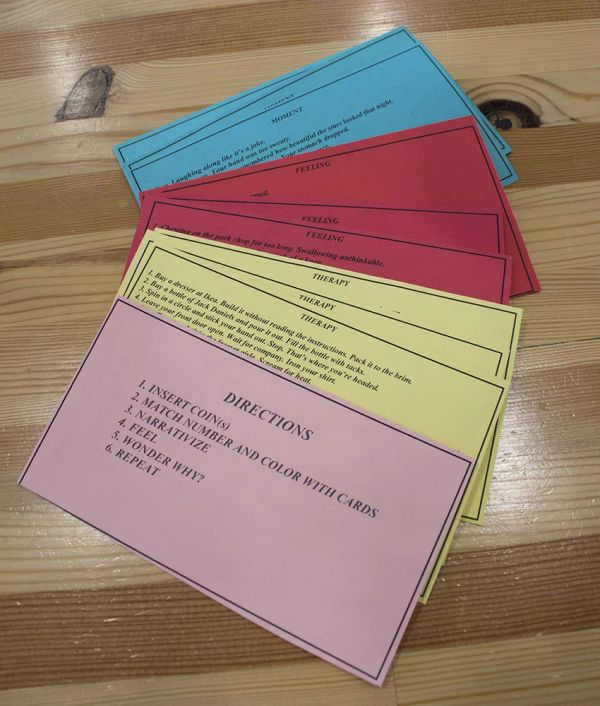

This object was original a learning toy for children, and it still is even after we’ve transformed it.Rather than teaching children how to interact with a robot to deposit and withdraw money, this object now teaches both children and adults how not be become objects themselves. We’ve broken the voice box, and the ATM is filled with shredded money made of lines of anti-capitalism poetry that can be organized and re-organized into many different poems. It uses a learner-centered pedagogy to demonstrate the human need to make meaning for themselves and that creation is only possible if all the money is shredded. In the age of automated capitalism, the greatest human need is to be more human.

About the artists

Begin

Hot glue, wax, pennies, shells, paper, tea, salt, dimes, plants, hinge

About the artists

Domestic Savings

What do we save? Money, of course. The quarter-sized slit cut into the top of this container was there to begin with, along with the copper plate on the side that reads “Coin.” This container makes no secret of its original purpose: a savings account, funded coin by coin. I started by expanding the definition of savings—asked, what do we save? Then I started to consider who, when, why, and how. The more pressure I put on the idea of saving, the more I kept coming back to a domestic space. We save so we can buy a house, fill it with furniture, have children, put them through school, retire, move to Florida. We save so we can begin to create a domestic space (a house, a marriage, a family).

Perhaps this is why, for me, the concept of ‘saving’ began to take on gender roles. More specifically, the idea brought me to my grandparents. Even more specifically, to their house. My grandfather saves by repairing, remodeling, fixing; my grandmother saves by repurposing (used to-go containers, used butter tubs), by collecting, by mending, and by remembering (names, dates, deaths, marriages, to-do lists, family lore, family history). My grandfather worked for forty years, and she balanced the books. There’s a way in which their roles epitomize two different kinds of saving: one, physical (fixing the broken gutter, depositing a check into the bank) and the other, emotional (picking up a stray button from the ground, keeping the sauce packets from a takeout order, keeping track of the money in the bank).

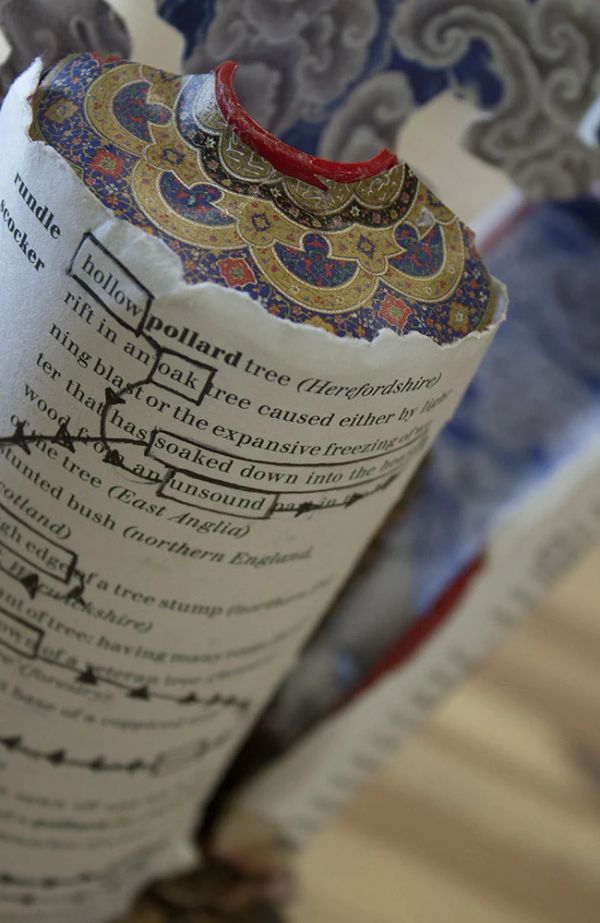

The outside and inside of my container are collaged with pages from a Reader’s Digest Complete Do-It-Yourself Manual from 1973. The outside deals with exterior DIY concerns (how to clean a gutter, paint wood siding, etc.), while the inside deals with interior concerns (mending broken pottery, repurposing a wine bottle into a drinking glass, etc.). The entire collage works as a kind of instruction manual, but not one that you can follow in any linear fashion. And not one that will lead you to any foreseeable final result. The important thing, in this DIY collage, is the process. It’s a broken process to encourage a closer examination of the process itself, and by extension an examination of the steps we go through to save our various things.

The container begins with the outside of a house, continues with the interior, and is continued further with two spools and pin cushion, meant to be a kind of sewing kit. For years, women have sewn in order to save. My grandmother has spent her life mending hems and sewing buttons on clothes for the rest of the family. The significance of the sewing kit, two spools unspooling unbroken text, is to position myself somewhere within a masculine and feminine savings--to push into my own understanding of domesticity and the act of saving. The text wound around spools, at the heart of the object, positions myself within and against two domestic roles, neither of which I’m ready to inhabit in full. As you unspool the text, you’re visually confronted with my process of learning a domestic task I never learned. My generation doesn’t expect a house, a retirement account, and we haven’t learned these simple domestic tasks of saving that my grandmother and grandfather grew up learning. I need a book to teach me how to install a window and a YouTube video to teach me to sew. The running stitch, as the video taught me to call it, is uneven, barely anchored at first. By the end of the second spool, my stitch is more practiced, more even, more confident.

About the artist

Brooke Schifano

Brooke Schifano is a poetry MFA candidate at The University of Massachusetts, Boston. She’s been a recipient of the Anne Fields Poetry Prize and has served as a poetry editor for Breakwater Review and Fourteen Hills. Her most recent work can be found online at Mortar Magazine.

Fire Safety Manual

Access, the haves and have-nots, and the way in which class forms and informs that access is something ever-present in my work.

I was struck at the thought of a bank in the form of a fire extinguisher, as both can be used to put out fires; the extinguisher in the literal sense and the bank (or at least the money within) in a figurative sense. A recent example of this during the devastating California Camp fire: To save their multimillion-dollar California home, Kim Kardashian and husband Kanye West used their means to hire a private firefighter to keep flames away. Money in the bank bought them access to a fire extinguisher—and this became one of the themes on which this piece would build—Who has access to the fire extinguishers of the world? And what does it cost those who merely have the plastic effigy? How far-reaching are the consequences of fires that do not come with access to a means to safely extinguish them?

The works within are poems that especially deal with that latter thought: how far has my own class and thereby lack of access burned me? How deep? How have I created ways to extinguish my own fires through art and how do I restrict access to my own ‘wealth’?

The figure inside can be manipulated/lowered to safety from these fires by sliding money through the bank slot. And in this same way, money keeps the figure down.

In addition to theming the piece around money and access, I wanted to use materials that had a connection to fire. Paper, pennies (the copper or nickel within), clay—the materials used in this piece were subjected to fire or extreme heat in some form or another and this interaction molded and informed the objects present in their current instantiation.

About the artist

Andria Warren

Andria Warren is an East Tennessee native, playing nomad around the Boston area while she completes her MFA in Creative Writing Fiction. Her work focuses on class systems, trauma, and animal companionship. When she isn’t writing, she can be found chasing animals, which she will argue vehemently is research, or photographing minutia that brings her joy in the wide world, which she will pretend is not research.

rally your marbles; a therapy machine

When we were first given the gumball machine, our thoughts immediately turned to memories of childhood: begging our parents for one more quarter and the urge to drown ourselves in sickly sweet emptiness. We knew we wanted to maintain the kitschy amusement of the gumball machine while acknowledging and interrogating the fact of exchange and money that is inherent in its operation.

As artists, we are both interested in ideas of memory and its application through art, i.e. art as therapeutic practice. We’ve also both been privy to the way in which contemporary, and specifically American brand of neoliberalism has warped ideas of self care. Not to mention the prospect of forgoing basic necessities to pay for professional mental health care.

We brought these ideas to the gumball machine, desiring to explore the potential for therapeutic art while also acknowledging the ways in which self care has been cheapened and fetishized.

Thus we have ‘rally your marbles; a therapy machine’.

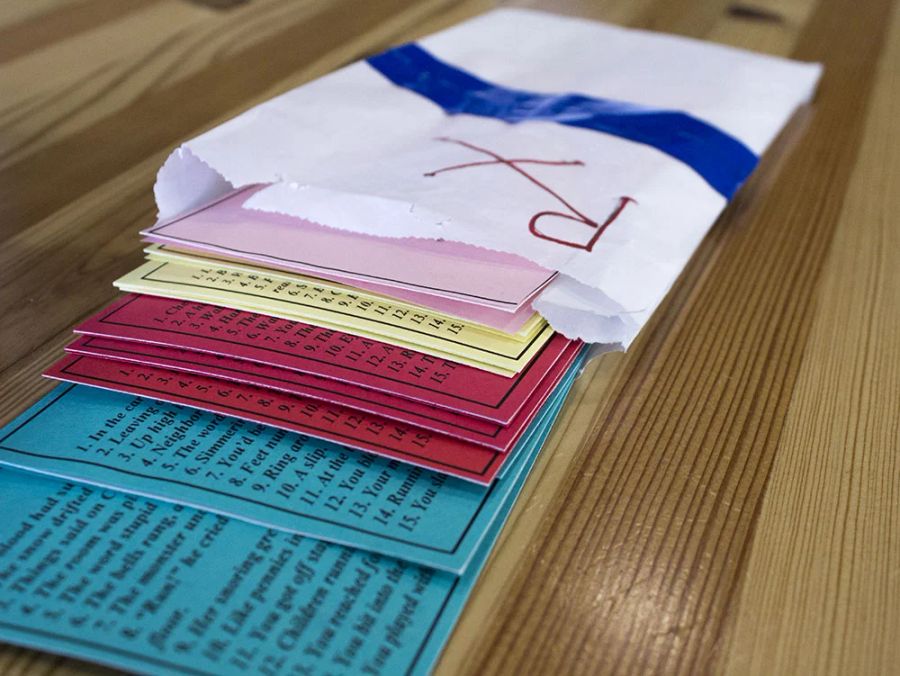

An object with multiple purposes, layers, and requirements if it is to work properly. First, the machine has a frosted glass globe which contains marbles. The marbles are painted to represent three types of content: Moments, Feelings, and Therapy. The marbles for moments are painted blue; the marbles for feelings are painted red; the marbles for therapy are painted gold. Each colored set is numbered from one to fifteen, and they are meant to point the reader to a corresponding moment, feeling, or therapeutic message found on a card located in an RX bag attached to the outer cover. The machine itself suggests the human brain and neurons firing; the cloudy glass the distortion of time and ego. With the outer box, we meant to emulate the kitsch of an old fashion television or arcade game.

Through this project, we hoped to explore the ways in which we often force the memories and moments from our past into narratives that make us feel better or lead us to something to make sense of the various violences and pastoral scenes of earlier times. This object asks the reader to engage with the mechanism by exchanging money for a marble that allows them to dive into the content. As a result of the randomness of this engagement, the reader must do the work themselves to cohere the different outcomes into a narrative. Ideally, this results in a reader who must then question their own conclusions about what the story is and why they think of it as such.

About the artists

Drew Bevis

Drew Bevis is a writer out of Boston. He believes a word is never stronger than when its grasp on its own meaning is weak. Find more of his work at _S/Word_, Mannequin Haus, and The Cafe Irreal. He believes everyone reading this should join a revolutionary socialist party as soon as possible.

Amanda Spencer

Amanda Spencer is currently a graduate student in the English program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is fascinated with how villains become villains and constantly users her writing to try and dissect the dichotomy between good and evil. Her hobbies include working on her young adult novel and hanging with her three cats: Peepee, Buttercup and Squiggles.

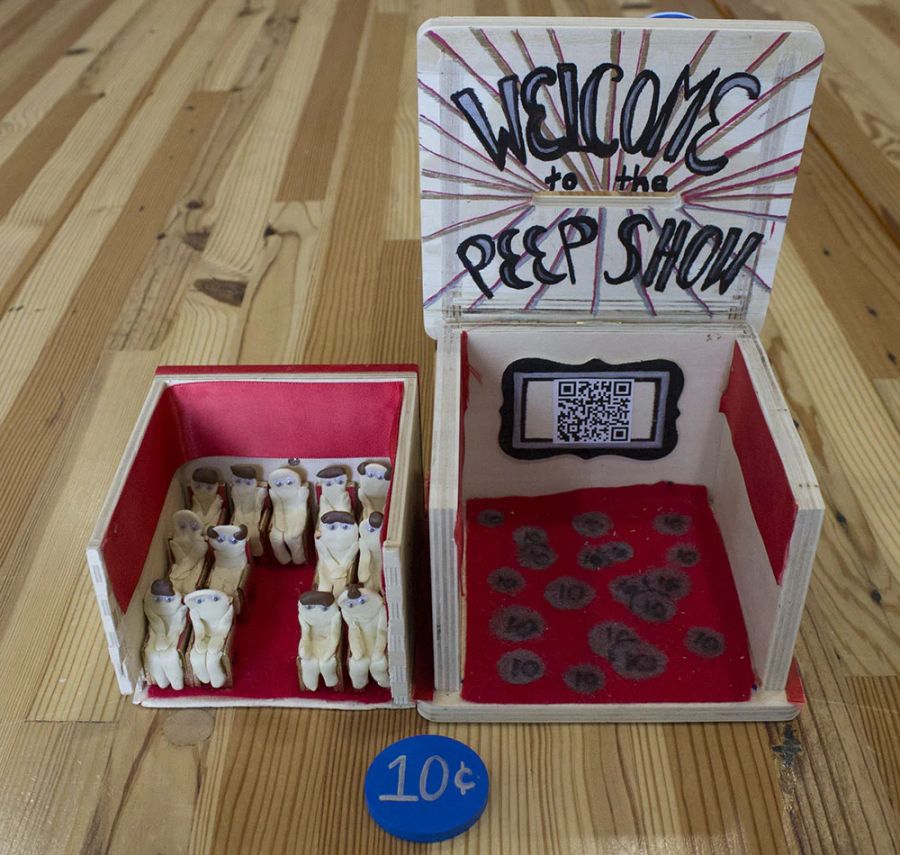

Peep Show

Peep Show explores the concept of the male gaze as it is experienced in the coming-of-age chapters of womanhood. Without taking a declarative stance on the portrayal of women in society, we, the artists, worked to portray the male gaze as we knew it to exist within our own lives: a male gaze that is duplicitous—speculative, private, innocent, and more sinister. Our book explores the nature of this “coming of age” period as one that exists in a liminal space between the outer world and the inner world, a space that is penetrable by men’s eyes as they seek access to more private spaces and project their own meanings and intentions onto those spaces.

The outermost layer of the object, the drawer aspect, is meant to serve as both an enticing, inviting, come-hither type of façade, while also harkening to the more innocent, child-like, dreamy aspect of our girly selves as we teeter the line between girlhood and womanhood.

Upon opening the drawer, and thereby reaching past the first layer of the piece, we begin to get to the heart of the thing, a heart that is filled with men who have also chosen to break past that initial layer of innocence, and we are therefore left in a space that is more dangerous, a more vulnerable place that is left to the mercy of the men’s eyes.

This brings us to the final layer of the piece—what the men are watching. As the viewer opens the piece, and unlocks the inner space, they will find themselves prompted to watch the same show as the men, which is accessible via QR code that is pasted to the “movie screen.” This movie directly mimics our, the artists’, experiences with the male gaze, as we portray the way we feel watched, the way our normalcy becomes sexualized. The video contains footage of what we consider our everyday lives—what our world looks like when we are just living, rather than trying to put on a show, but pays homage to the idea that, in a way, we always feel that we are being watched.

And this watching of the “movie” brings us right back to the beginning, the feelings associated with opening the drawer in the first place. Any viewer will be prompted to open it, to see what’s inside, though the drawer represents privacy and secrecy. But those needs to access the drawer, to take a peek, pay homage to the more sinister means of access that the men represent, a type of voyeurism or violation of the women on the screen.

Our book tells a story, but, most importantly, it tells our story. Our book grants meaning and understanding to experiences we have had in our own lives. Our book offers other women a chance to recognize their own experiences, to create an object of solidarity. And, furthermore, it gives those women a chance to turn the tables, to project their experiences onto the scene before them, whether they recognize them or not, and gain control over the men seated in the theater—to objectify them, look them up and down, put them on display, this time.

About the artists

Jessamyn Wolff

Jessamyn Wolff is a poet, visual artist, and an MFA student at UMass Boston. She is originally from Western Michigan and received her BA and Certificate in Creative Writing from Central Michigan University in 2017. Her work has appeared in Pork Belly Press and most recently in Hanging Loose Press.

Jacqueline Rosenbaum

Jacqueline Rosenbaum is currently an MFA student studying prose at UMass Boston. She is originally from Long Island and received her B.A. from Vassar College in 2016. She was granted Runner Up in the 2018 Haunted Waters Press Fiction Open for her story “Tennis Lessons,” which has since been published in their annual literary journal “From the Depths,” and her story “A Table Set for Five” is set to be published in Adelaide Literary Magazine in Spring 2019.

Reclaimed

Miniature toy fire hydrant, mixed media with paper, U.S. penny currency.

About the artist

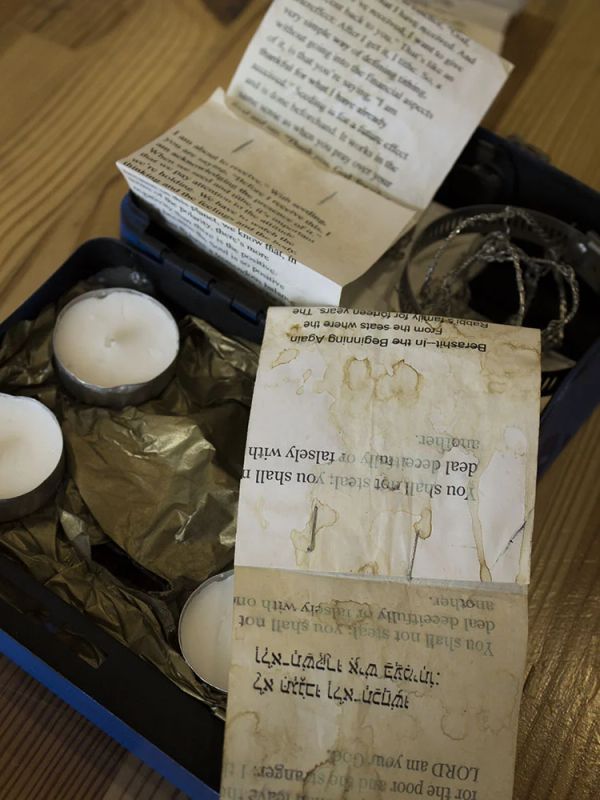

Ritual Savings

Our shared interest in ritual was apparent to us in our partnership, and found a home in Ritual Deposit. Kyéra’s work attempts to capture the gravity and import of the ‘mystical’ and seeks to unite the mind with the processes of the inarticulate body, a unison that naturally leads her to ritual. Sarah’s first thought on receiving the object was of the Pushke, or charity box, in Ashkenazi Jewish tradition. Rabbis teach that the act of giving is not about you; it is about creating and participating in the fabric of society. Any act of giving contributes to making community, a value that far exceeds typical commodified exchange.

The U.S. economy - predicated on exchanged goods, derived from exploited labor - fails to tell the entire story of valued exchange. Here enters the inalienable object: objects or possessions that go beyond transactional commodities. These cultural goods are not exchanged but circulated. Rather than symbols of monetary worth, these objects consecrate a social assemblage of heritage. The process of creating these ‘objects’ involve a ritualistic outpouring of tradition, passed down through generations, imbuing the object with layers of meaning. The inalienable object, forged through community ritual and time becomes a repository that reflects the distillation of culture and legacy.

Drawing on the way that ritual knowledge circulates, and runs parallel to economic exchange, Ritual Deposit seeks to capture the process of ritualistic creation. Like the interaction with the Pushke, Ritual Deposit invites the reader into a migratory journey for belonging that begins with a setting of intention. As prayer and penny unite to habitualize the act of giving, entrance into Ritual Deposit engages the reader’s ‘token of intention’ on a journey through weavings of Afro-Caribbean migration, and knottings of Halakhic remembering in search of home and belonging. In moments of need, the reader opens Ritual Deposit to find a repository of intention. Light a candle, breathe as you contemplate the night sky, relax and read the receipts of personal ritual and religious traditions. Contrasting the logic of the cash box, Ritual Deposit rewires ‘economy’ from simple accumulation into a synchronous multiplicity of culture and legacy, inviting the reader, through ritual, to a discovery of ‘home.’

About the artists

Kyéra Sterling

Kyéra Sterling is an MA candidate at the University of Massachusetts Boston where her research interests center on literatures of the African diaspora and the excavation of spiritual traditions as community cultivating practices among the displaced. An aspiring filmmaker, Kyéra’s academic research informs her cinematic genre and approach. Following the threads left to her by her ancestors, she is currently producing her first short film Witches That Marry in the Rain.

When not filming, writing, or researching, Kyéra serves as Chief of Staff in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

Sarah Shapiro

Sarah Shapiro is a poet and visual artist whose current projects explore (dys)abilities poetics, feminist walking, place-making, and New Deal Post Office history through concrete poetry. She is a poetry MFA candidate at University of Massachusetts Boston and teaches there, as well as at Suffolk County Correctional Facility.

Sarah’s first chapbook The Bullshit Cosmos is forthcoming, July 2019, with ignitionpress. Her poems have appeared in TIMBER, glitterMOB, She Grrrowls, Bunbury, and Poetica Magazine. Her visual work has been featured at BAAA Gallery in Cambridge, MA and she has completed a residency with Cove Park, in Scotland.

Safe Space

We were originally provided a teal Toy Locker Safe for repurposing. Given that the object’s original function as a safe was to house coins and monetary valuables, we decided that we would continue emphasizing the concept of value in our object. We wanted to call into question the idea of value as a primarily monetary concept. We spent some time brainstorming about other kinds of value(s) and what kind of a space could hold these other, non-monetary valuables. Specifically we asked: what do we value, why do we value it, and what does value look like when it is separated from the monetary? In considering these questions, we concluded that we value memories, experiences, and processes--the stuff of life that is attached to quality of time spent, with that itself (the quality of time spent) being our most precious commodity of all.

In thinking of how this object could be repurposed, we realized it first needed to be renamed as Safe Space. This title grounded us in our intentions for the project, allowing for a more expansive definition of “safe.” Our new definition of our given space therefore nodded to the monetary, while also including what we considered to be of ultimate value: the priceless need for mental, emotional, and physical safety, especially in turbulent times.

The combination lock in the Toy Locker Safe, along with the accompanying keys influenced us to display the contents of the Space in a manner that visually continued to play with the original monetary function of a safe. We therefore spray-painted the teal locker and some of its contents (its inner white storage area, the keys, the Safety Scissors) gold. We also chose items for the interior that fit the gold theme. Furthermore, we maintained the object’s original function as a locker, as the Safe Space allows for the housing of personal paraphernalia, much like a school locker.

Given that we decided to retain this nod to both the school locker and the monetary safe, we didn’t want to transform the object entirely; rather, we wanted to transform its purpose. The fact that the Safe Space includes a small coin slot at its top made us wonder what else could enter the Space through this slot. The idea for the Daily Keep-Safes was born out of this consideration. Users of the Safe Space can write down things valuable to them on small slips of paper (the Daily Keep-Safes) and insert them through the slot for safe-keeping. The Safety Manual instructs users that these Daily Keep-Safes could be used to jot down memories, dreams, wishes, secrets, ideas, the names of loved ones, daily occurrences, and much more.

It seemed obvious to us that our Safe Space would require a Manual for use. The provided Safety Manual guides users’ interactions with the objects within, including their personal Daily Keep-Safes. We drew from personal traditions and experiences to create the Manual, referring to our own individual practices of safety that we could share with the user. These personal practices are culturally specific to our personal histories. The Safety Manual is a loose narrative of the object’s possible uses, guiding the user to interact with the Safe Space contents and their own personal treasures.

For one of us, seeking and maintaining safety is of paramount concern. For the other of us, safety is a boundary to be stretched and crossed. In co-authoring the Safety Manual, we hope that the user will find themself pushed in opposing directions, encountering the intersection of each of these polar opposites. In doing this, we have called into question what we individually consider safe or unsafe, and also the concept of safety as a whole--thereby allowing users to formulate their own understanding of safety within this spectrum. We therefore imagined our intended audience/user to be anyone seeking to interrogate these notions of both value and safety.

The Safe Space includes a compact mirror glued to its interior and nestled behind a velvet curtain, a velvet lining for a rich sensory experience, a jar of ginger and sage tea, a jar of rosemary and lavender for smelling or burning, a bell for initiating and ending Safety Sessions, a pyrite crystal, a battery-powered candle, a string of small beads, safety pins attached to a tulle entry curtain, a small teacup for use with the tea, a glue stick, and a pair of safety scissors. The user is instructed to use each of these objects in a variety of ways by the Safety Manual. The Safe Space itself is protected by a bubble-wrapped Safety Bag, which the user is encouraged to hug to their body while transporting their Space. Additionally, Safety Eyeglasses and Safety Gloves are provided for mediating the user’s interactions with the Space.

About the artists

Christie Towers

Christie Towers is a current MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Her work can be found in Narrative Magazine, Nimrod, Belle Ombre and others. Her work was selected to be featured in Ted Kooser's project, American Life in Poetry, forthcoming in 2019.

Krisela Karaja

Krisela Karaja is a Master of Fine Arts candidate in Poetry at the University of Massachusetts Boston, where she teaches sections of composition and creative writing. She is a former US Fulbright Research Fellow to Albania and she works in translation from Albanian to English.

All This Will Someday Be Yours

All This Will Someday Be Yours began with the object we were given as a part of this project, which at first glance we interpreted as a lockbox—a container for important financial documents and memorabilia that’s kept safe in a family home against burglary or fire. The locking feature was of interest to us, as it signaled both the possibility of privacy as well as security, two concepts which interact in countless interesting ways when applied to interpersonal/family relationships. In particular, we were interested in exploring the ways in which memorabilia served as narrative markers and to explore the ways in which relationships operate within capital. We use common means of documenting lived experiences, particularly annotated photographs and heirlooms, to explore these themes.

This box itself is filled with annotated photographs that document a fictional narrative of two people—whom we’ve named J and B—coming together and apart. Half of the photos are captioned with fictional events, many of them are captioned with headlines from American news outlets between 1999-2010, and a handful are captioned with quoted passages that inform or discuss our lives under capital patriarchy. We keep these photos roughly in order, interspersing the theory quotes and headlines between the chronological series of fictional events.

Inside the lid of the lockbox are three heirlooms—a 2000 Sacagawea $1 gold coin, an engagement ring with the stone pulled out of it, and a USB drive full of financial documents and birth certificates – all of which are, at this point in the narrative, corrupted. These documents/memorabilia explore how this box functions as a container of legacy, of items, narratives, and debts that will be passed down to future generations, as implied by Eve, the offspring of J and B’s relationship in our narrative. We are interested in the ways in which this inheritance is inevitable, how one cannot ever fully escape the material, social, and kinship relationships and circumstances in which one grows up. We have sealed the key to open the box under the title label so that the reader/inheritor is required to “break into” the object in order to engage with its contents, in the same way that any breach of security – whether interpersonal, economic, or physical – requires an intentional rupture.

About the artists

Julia Lattimer

Julia Lattimer is the Editor-in-chief of Breakwater Review. She was most recently named Editor’s Choice in the 2019 Sandy Crimmons National Prize for Poetry. She runs a monthly queer poetry reading series and is an MFA candidate at UMass Boston.

Daniel Elfanbaum

Daniel Elfanbaum is a writer from St. Louis who now lives outside Boston with his fiancée and their cat. He is currently a candidate in the UMass Boston MFA Program in Creative Writing.